21 November 15 – Saturday – DAY FIFTEEN

At the orphanage I get some kitten action immediately. They’ve got a number of stray felines that wander in and out all day. Sister feeds them – usually chicken, and very often steamed rice, which they seem to eat just fine. They’re kind of skinny compared to spoiled American pets, but they also seem healthy. Kind of like everyone in Myanmar to some degree. The cats sleep with the children at night, and they’ve given them all crazy names.

As a chorus the littlest kids tell me that the tiny kitten I’ve been able to chase down and hold is named “Itti.” It takes me a while to realize that the cat’s name is “E.T.,” and that he is named after the hideous Spielberg alien because the kitten’s head is so strangely shaped. They think he looks like E.T. Another is named “Yellow,” in English, just like that. We don’t get the other names, but Cecilia and I have named one “Eyeliner” and another “Eyebrow,” for some similar reasons you can probably divine fairly easily.

Tinmar Aung is glad to see us, even after only a day’s break. We can tell that she tells all the other kids stories about us, so now is the time that she can have proof of all her claims.

The orphanage is a three story building set right next to the school. As in one building over, with their backsides adjacent. The roads there are all unpaved, just a series of deep ruts in dirt that must be miserable to transverse during the rainy season. The countryside is lush and green, and cows wander in and out of everyone’s property.

Today there is no electricity at the orphanage. A generator not-so hidden by a wooden enclosure sometimes provides backup power, but they seem to be out of fuel today. There are animals everywhere, it seems. Not only are there the obvious cats, but they have a dog – named possibly Snowy or Snowball, or even something else because they all seem to say it differently – chickens, pigs, rabbits, and some other birds in an aviary. Rainwater is collected from the drains on the roof into a large cistern, and this is used for washing and laundry. The children do chores, but they also tend a small farm in the back where they raise vegetables for their own table.

Sister greets us and we’re led inside for more talking and eating fruit. There are two thirds as many girls here, and it seems as though many of them, as they get older, work in the kitchen. They are very attentive and almost servile – which makes me feel uncomfortable. I’m not only not a fan of servility, but I think of myself as being over fortunate compared to the orphans – that they would be waiting hand and foot on me seems ridiculous – it should be the other way around if anything. I’m exaggerating, of course, because no one is a servant here. It’s just that I’m sensitive to these kinds of things.

We tell Sister what we’re up to, and she is more than helpful. The entire grounds are open to us, and we should ask if anything would help the film. The children have chores to do, but they enjoy lots of free time, and they are curious and would like to help out – which ones are not too shy to do so, of course.

We go straight to work, shooting Tinmar Aung doing her usual chores – sweeping the front, helping the others, preparing lunch – and we get plenty of the other kids while we’re at it. Gavin shoots loads of B-roll of the environs: the animals, the buildings, the little kids while they nap. Everyone is extremely friendly and cooperative. The kids are kind of fascinated by us but – unlike the school kids – they are extremely respectful and go to some lengths to pretend we are not there while we roll.

As the day progresses we’re starting to get to know these kids, although we do not know many of their names. We do learn that one girl is also called Nyin Zar Wai, and it makes us wonder about the origins of that name. Cecilia has taken a liking to a tiny girl she calls “Resting Sad Face Girl,” because her expression always seems so incredibly sad. We’re certain this girl is not actually sad all the time, but she sure looks it. A lot of the younger kids have been shaved recently – we surmise this is because of lice. The older ones can be expected to take care of their hair a bit more, but bugs are a danger with the smaller ones.

We learn about Tinmar Aung’s best friends at the orphanage – the two or three girls who always hang around with her. And we’re similarly interested in the tomboy who seems to be around to do heavy lifting and other hard chores other kids don’t want to do. The day passes easily and thoroughly enjoyably, Lunch is delicious, cooked by the girls and featuring vegetables from the garden. There are plenty of bananas, as usual. Once again, we feel kind of guilty getting the best food here. What do the 58 orphans here get to eat? We know it’s not as good as we just had, because every opportunity Tinmar Aung has to wolf down our snacks she takes immediately. We know they are well cared for but our meals must seem special to them, and that does not sit well with the group of lefty egalitarians that we happen to be. But what’s to be done? Throw up your hands and scream at Sister? When in Rome… but believe me, I’m resolved to give back whatever I can whenever I can to these kids. And of course that will start with our gifts and Gavin’s donations to the orphanage.

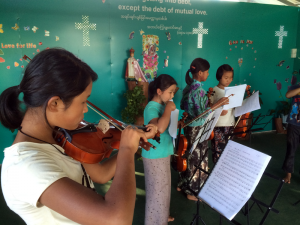

As it turns out, there is violin practice of the orphanage. Tinmar Aung is also among those who meet at the roof of the building and play in the open air. The kids are awful, scratching through Xmas carols and, as luck would have it, “Ode to Joy”. Why religious people have claimed that apostate Schiller’s poem is beyond me, but it sure it has something to do with seeing good writing and knowing it when you read it. Or perhaps that Schiller’s commitment to humanism has its appeal when religious dogma is cast aside? Gavin obviously enjoys the weird juxtaposition of Beethoven’s 9th in the middle of Myanmar.

Though the music is scratchy and terrible (which is to use that word in the sense of “causing terror”), the footage is great. The violin teacher has brought her little daughter along – dressed in a little princess gown and made up like a Korean fashion model. I guess the teacher expected her prodigy to be on camera at some point. More embarrassing, the princess leadenly pounds through a couple of hymns on the organ – mechanical and empty of all interest. The awkward comparison between this pampered monkey and our plucky heroine – not to mention her impoverished brothers and sisters – could not be more starkly portrayed. Gavin records a bit, but they shut the camera off after a while. We’re polite, at least.

That night we get ready to light balloons. Just as the balloon festival is a huge city event, it’s also practiced privately – like 4th of July fireworks. Many people light their own balloons, and you can buy them pre-made in the market. Cecilia has already closed down a few places buying all that they had, and when the sun drops low in the sky Sister and the girls prepare a bonfire in front of the orphanage.

Yes, why are there no older boys to help out with this kind of thing? Sister says that the older boys run away. There’s nothing to keep them at the orphanage – they do lock the gates at night, but that’s not a maximum security issue, it’s just a formality in some ways. A clever boy can scale the wall immediately. She’d like them not to run off – she feels that they probably only get in trouble anyway. But what can you do?

Here again, I’m struck by Sister Mary’s incredible pragmatism. Doing good works is just that – you do the good deed and you ask for nothing in return. Sure, it’s a Catholic orphanage, and there’s plenty of Jesus around. But if you’re not into it, you’re not forced to pray, or even made to sit down with everyone while they do it. Of course if you’re not praying, you COULD help out with some chores around the place. But here again, I see no one forced to do anything.

Sister does discipline the kids. We know Tinmar Aung has had her knuckles rapped for not keeping her fingernails clean. Corporal punishment never sits well with the contemporary Westerner, but I can see the ends justifying the means. Hygeine is important, cooperation is important, and community is important. You cannot run an orphanage without certain rules in place. You cannot raise 58 children no one else is bothering to raise without establishing some kind of order.

And there is a string sense of self-reliance here in Myanmar that I’ve mentioned before. These kids not only know how to wash their own clothes by hand, they are comfortable washing other people’s clothes – doing what they can for other people in order to live together in some sense of harmony. They farm and raise animals, not just because this helps defray the costs of feeding all of them, but because the exercise in accountability and common goals also makes them better people. And Sister knows this – at some level the most profoundly heartfelt Catholics are all socialists and communists. Because the head of their church was one. I wondered how spoiled white kids in some Pacific Palisades school would do here. Sure, they may have some kind of garden at their fancy school, but they’re not relying on it for their dinners. And they’re not feeding chickens so they can snap their necks and boil them up later. Who would win in a fight? My money’s on Myanmar.

As the sky darkens the bonfire roars, with flames five feet high. The kids love to sing, and they’re doing so now – a passel of campfire songs many of which are familiar to us. Gavin sets up the balloon lighting sequence. Sister’s done this a million times, but so has Thiha, and he’s actually pretty excited about it. He hangs back, though, letting everyone else muddle through before he comes in and shows us how. The balloon itself is thin plastic, like a dry cleaning bag. They are about six feet across, but there are larger ones.

Below the opening of the balloon is placed a small wire-bound bundle of pitch-soaked wood. You burn the wood and hold he balloon above it, filling with the hot air until you can let it go, where it sails above the houses and trees. Coming from Southern California, we are all a bit horrified. So… you let go of a burning pile of wood, which floats in some direction? To fall on whose house? No one here thinks anything about that at all.

Sister thinks there’s not enough flames. I think she may be a secret firebug. But she and Thiha get two balloons going, and – with shouts of joy from the kids, they are released into the cool night air. Sean catches it all. Except Tonmar Aung’s reaction, which is sort of essential. Gavin is miffed. Despite the impossibility of watching the balloon flight and Tinmar at the same time, he is still a bit worked up. We clam him down, though – the night is young, we have plenty of balloons, and Tinmar Aung shows no signs of even noticing the camera. Her reactions are going to be just fine on a second round.

We try to get three balloons going, but that’s too many. John steps in and tries to get the evil-looking monkeyface balloon going. Despite Thiha’s instructions, John fills the bag with cool night air first, and then gets the fire going. The nefarious monkey flops around as it fills, the mixed warmish air inside not enough to raise it. Thiha’s balloon is released, and it flies away… only to hit the roof of the house next door. It’s a tile roof, so not much worry about the house going up. Thiha rushes over to tell them about it with predictably blase results all the way around.

Meanwhile, the evil monkeyface continues to misbehave. It twists and contorts, neither buoyant enough to take off on its own nor placid enough to stay in place while it is properly filled. John releases it. And it goes straight into the over 100 year old avocado tree right in front of the orphanage. Now we’re scared. Visions of this beautiful tree going up in flames and the orphanage burning to the ground because of the evil monkeyface flash through my head. Fortunately things are not so dry here in Myanmar, and the balloon sputters out harmelssly. Everyone laughs.

Then the kids sing – a repertoire that goes on so long we stop shooting in the middle of it. They know all the words, and those songs that have funny gestures or calls-and-response seem to get the best participation. When there’s a song we know (some are actually in English it turns out) we join in, and Cecilia and I even do stupid dances with them to make the kids laugh. Sister takes their fun pretty seriously, usually tying it in with Catholic feast days and holidays overall. You could do much worse with your life than growing up in this orphanage, rough as it is.

And somehow Sean managed to miss all the balloon lifts. The key, crucial moment of releasing the balloon is in none of the footage. There’s lots of other stuff. Gavin is perturbed. It’s funny – Gavin does not really get “angry” per se. He may raise his voice, which also becomes higher and squeakier when he does. He is exasperated, irritated, confused, miffed, and a whole host of other things. But he is not “angry” in the classical sense.

At the hotel that night there is a huge confab about it all. Sean is upset about Gavin’s expectations for the shoot, including these major sequences at the school and during the balloon lifts. It’s true; whether he knows it or not Gavin has totally set up Sean for a weird kind of failure. He has not told him in uncertain terms what he wants, figuring that Sean will ‘find it.” So far Sean has never “found it,” and has always rejected the idea that he ever could. He’s a lot more literal-minded, and he would appreciate some instruction.

They are up till 1 AM with this kind of talk, and despite the volume, I sleep almost immediately. That is, only after naming yesterday’s AND today’s files. If I don’t keep up with that it will be out of control. and I’ll be very sad when we get back.

As it is, I’m crippled for two things I really need on this shoot. The first is that the recorder names everything poorly. The files must be renamed by scenes/shot/take and by whose mic (character/boom/etc.). That takes some time, even though I have some software tools to help with the naming conventions. The second is that the recorder is not capable of sending out a 2-track production mix. So at some point I am going to need to make mixdowns for editing. I’m not doing that right now, as it would be prohibitive on my time. That will have to come later in LA, so it’s even more imperative I know what the files are for when I’ve forgotten all this.